In Retrospect: Curated Film Memory in Paris Cinema Retrospectives

Written By Polina Bryan

Image Credit: Polina Bryan

As dusk falls upon Paris on a Sunday in September, the city becomes steeped in the honey-colored light of streetlamps. Amplifying murmurs from queues lining quiet alleys of the Latin Quarter seep from around the corner. A growing crowd of fashionable, chattering, cigarette-smoking young people outside one of many iconic Parisian arthouse cinemas are awaiting their showing. A young man in a dress shirt sits behind glass, manning the ticket booth. Despite the air of excitement and anticipation, tonight’s film is not an exclusive new release, but Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere released in 2011. Today’s installation is a part of the nearly one month long Coppola retrospective at the Cinema Saint André des Arts.

Image Credit: Polina Bryan

We can recall how the Barbenheimer phenomenon of 2023 had us planning trips to the theater, and more significantly, talking about it with the people around us. Not only did the experience of watching the film itself feel back, but people felt an excitement to be physically back in the theater. Like most pop culture waves of the past five years, it rose, crashed, and now feels as if it has returned to a standstill as we wait for the next niche film spectacle; the next time we can go to the theater in an on-theme referential outfit, identify and participate in the aesthetic world of a film, and go to the theater just to say we did. It feels as if people who care about film enough to discuss it have reached a relative consensus that the age of biopics and film adaptations regurgitating familiar stories is quickly growing tired. But what is different about these Parisian retrospectives, showcasing films we have either seen before, or, have access to from home? If we are so bored by what we have seen before, why does revisiting cinema’s past here feel so alive?

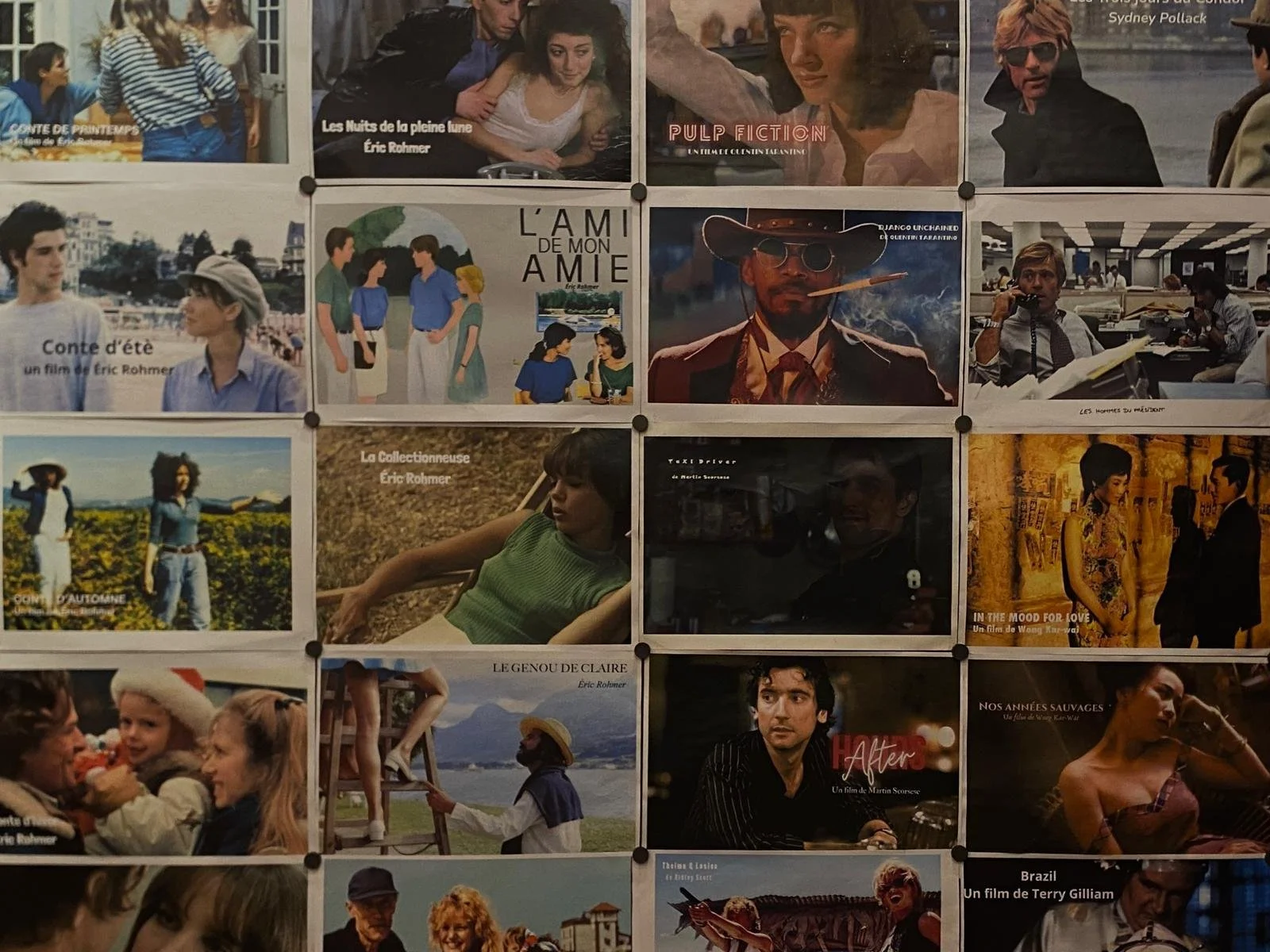

Earlier this year in an article published by Le Monde, it was reported that France’s filmgoer rates are on track to recover to pre-Covid figures, standing in stark contrast to other major European countries and the United States. In the land of the Lumiere Brothers and Cannes Film Festival, film-going, beyond simply film-viewing, is a social ritual. While unfortunately fading elsewhere, cinema is able to absolutely endure here. It seems to be the reason why so many cinemas like the Saint Andre des Arts, Christine Cinema Club, and La Filmotheque du Quartier Latin all feature weeks long homages and tributes to film legends like Wong Kar-wai, Frank Capra, RobertRedford, Stanley Kubrick, and more, not to mention the plethora of one off showings outside of any formal retrospective programming.

Image Credit: Polina Bryan

These hardly feel like mere exercises in nostalgia or cashgrabs for these cinemas. To me, they have revealed something deeply romantic about Paris’ relationship to time and memory, where it’s not a matter of looking backwards, but of circling back again and again to find something new each time. What’s more, is the sheer opportunities for discovery that these programs propose. The younger audiences I see at these cinemas always strike me. I think that these screenings must be an initiation of sorts, a first encounter with a cinematic past in its intended form. In the age of endless viralized entertainment, unfortunately, the act of returning and rewatching can feel subversive.

Beyond discovery, the collective experience of watching these films both cultivates and encourages a spirit of shared conversation and debate. Later this month, the auditorium at the Louvre is hosting From David to Kubrick, the Revolution and Empire on the big screen, a 10 day film festival of eleven screenings accompanied by debates and meetings. Just last week and set to carry on until the end of November, the Orson Welles retrospective at the Cinematheque Française began, featuring not only film showings, but presentations and conferences too. Also at the Cinematheque, a series on 38 year old French actress and screenwriter Hafsia Herzi, featuring a formal presentation on her body of work. The active dialogue created around these works defiantly challenges the growing feeling as of late that film and cinema are a disposable one time use media, a fleeting visual moodboard of our time, and onto the next. Perhaps we should not see film for what it says about our time, but what the film’s time is able to say about us, living on through these thematic threads. Moreover, the reverent treatment with which the French approach a catalogue of works of a director or actor through these programs starkly contrasts the mainstream tendency we see of piece-driven consumption, opting rather for artist-driven consumption. These retrospectives demonstrate the attention to the trajectory of an artist, the threads that connect one work to another, the evolution of a vision.

Image Credit: Polina Bryan

There is no shortage of independent cinemas and film institutes offering these programs in Paris. Their sheer density and accessibility in the city make it possible to stumble upon a screeningalmost any night of the week in the Marais, Montmartre, or the Latin Quarter. The value of cinema in France is clear through the status it has in French cultural policy, in the fact that theaters themselves continue to be subsidized by the government, whilst cinemas across other parts of the EU and the United States continue to shut their doors. Paris feels unique as a city thathas not only preserved its movie houses but its movie habits. Cinema remains woven into the everyday, not as luxury or nostalgia but conversation.